Hardball and History Deter Betting in Baseball

Photo Illustration by Bill Hyden

By Brown Burnett and Bill Hyden

“I’ve loved baseball ever since Arnold Rothstein fixed the World Series in 1919.”

-Hyman Roth in The Godfather II

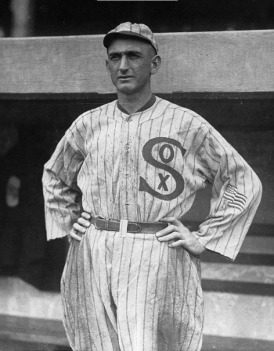

The roots of Major League Baseball’s disdain for gambling go back to the 1919 World Series when the Chicago White Sox admitted throwing the best-of-9 series with the Cincinnati Reds. The scandal was quickly followed by MLB’s Rule 21-d:

(d) BETTING ON BALL GAMES. Any player, umpire, or club official or

employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in

connection with which the bettor has no duty to perform shall be declared

ineligible for one year. Any player, umpire, or club or league official or

employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in

connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared

permanently ineligible

“The wording has been tweaked over the years, but the core of the rule has been in place for decades and decades,” said MLB’s Media Relations manager Mike Teevan.

In the history of MLB, 19 players have received lifetime bans for betting on the game and eight of those players were 1919 White Sox.

According to Eliot Asinof’s 1963 book Eight Men Out, Arnold Rothstein, a professional gambler with underworld ties, offered White Sox players $10,000 each to fix the 1919 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Shortly after reaching an agreement to take the money, the White Sox players realized that Rothstein might renege on the agreement, but the Sox lost to the Reds 5 games to 3.

A 1921 grand jury found the players innocent of fixing the Series, despite their confessions of taking money from gamblers, but MLB’s newly appointed Commissioner, former federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, permanently banned the players. MLB.com says baseball’s ‘commission’ of owners gave Landis unprecedented power, allowing him to:

investigate, either upon complaint or upon his own initiative, an act,

transaction or practice, charged, alleged or suspected to be detrimental

to the best interest of the national game of baseball, (and to determine and take)

any remedial, preventive or punitive action (he deemed appropriate).

In an effort to restore crediblity to the sport, baseball owners also said the commissioner’s decisions would be final and that the clubs could not challenge the rulings in court.

The SportingNews.com says Landis cited the players’ admission to having ties with professional gamblers as the reason for the lifetime sentences.

Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game, no player

that entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player that sits in a

conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and

means of throwing games are discussed, and does not promptly tell his club about

it, will ever again play professional baseball.

One of those players from 1919, ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson, remains the most accomplished of those 8 banned White Sox. In a 13-year career with the Athletics, Naps/Indians and White Sox, Jackson compiled a .356 career batting average, which remains the third-highest all-time average behind Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, making him a likely candidate for the Hall of Fame before the scandal. According to MLB documents, Jackson, like his other teammates, admitted taking money for his role in altering the series outcome. But he still led his team in batting during that World Series with a .375 average.

Landis died in 1944, and when A.B. “Happy” Chandler became Commissioner in 1945, clubs gained the right to challenge the Commissioner’s decisions.

Today’s Major League Baseball (MLB) doesn’t prohibit players from gambling on other sports, but major leaguers quickly learn that MLB discourages it, according to Teevan who says league conduct presentations routinely center around Rule 21-d, of the player’s misconduct code.

Former U.S. senator George Mitchell’s 2007 Report to MLB Commissioner Bud Selig about steroid use in baseball, commended MLB for posting signs referring to Rule 21 in all major league clubhouses and providing dramatic, role-playing presentations about gambling. Mitchell suggested that MLB do the same in regards to illegal performance-enhancing drugs.

“Our security and facility management department works very closely with each team and its players during Spring Training on a wide variety of issues,” Teevan said. “Our annual Rookie Career Development Program, which is a joint venture between MLB and the Players Association, also touches on important issues with the top prospects from all 30 clubs, and education about gambling is a subject during the presentation.”

Teevan said many officials in the league’s security and investigations departments have experience in law enforcement and that there’s a reason to closely monitor gambling habits of players.

“Gambling is considered an area that could lead to other activities that could affect players’ careers as well their freedom,” Teevan said.

“For educational purposes, for clubs and players, we have used outside speakers who have addressed gambling experiences as a part of our rookie program.”

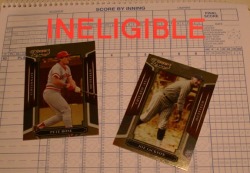

In 1989, baseball’s all-time hit leader, Pete Rose, joined Jackson on the lifetime ban list when the late Bart Giamatti tossed him out for betting on games in which he played and managed . Rose collected 4,256 hits over a 24-year career with three clubs, and like Jackson, was considered a strong candidate for the Hall of Fame before the ban. He’s the last player, or manager, excommunicated from the game. Prior to Rose, the last MLB figure to be permanently banned from the game was William Cox, owner of the Philadelphia Phillies, exiled by Landis in 1943 for betting on his team’s games.

Rose admitted that he placed bets on his teams in his 2004 book, My Prison Without Bars. but has never officially admitted it to the Commissioner’s Office, so the ban remainsm barring Rose’s participation in any MLB activities.. Rose regularly makes appeals to his fans on peterose.com about lifting the suspension and now owns and operates a souvenir shop in Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas.

National Baseball Hall of Fame communications director Craig Muder said although his organization is independent from MLB, Rose and Jackson are banned from recognition, as well as acceptance, in that shrine, located in Cooperstown, N.Y.

“Pete Rose and Joe Jackson, along with a handful of other players are on baseball's ineligible list,” Muder said, adding that the Commissioner’s decisions on such matters also applies to the Hall.

“Our board of directors feels that it would be incongruous to have a person eligible for the Hall of Fame when he or she is not eligible to participate in organized baseball in any other way,” Muder said.

Last August, when efforts to bring back Rose were rejected by Selig, former MLB Commissioner Faye Vincent, Giamatti’s deputy at the time of Rose’s expulsion from baseball, told Paul Caron of CNN.com that MLB has never reversed lifetime bans.

"Nobody who has ever been thrown out of baseball has ever been reinstated. An owner, the 1919 White Sox, you name it,”said Vincent. “No matter if it's a third-base coach or an all-star, Hall of Fame-type player."

Vincent, who died last month at 75, said he thinks most major leaguers understand the lifetime bans.

"(Hall of Fame pitcher) Tom Seaver once asked me, 'If I'm a Hall of Famer, and I bet on baseball, do I get the same treatment?' I said, 'Yes.' Tom said, 'I get it. If you didn't do that, we would all bet on baseball."

“I’ve loved baseball ever since Arnold Rothstein fixed the World Series in 1919.”

-Hyman Roth in The Godfather II

The roots of Major League Baseball’s disdain for gambling go back to the 1919 World Series when the Chicago White Sox admitted throwing the best-of-9 series with the Cincinnati Reds. The scandal was quickly followed by MLB’s Rule 21-d:

(d) BETTING ON BALL GAMES. Any player, umpire, or club official or

employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in

connection with which the bettor has no duty to perform shall be declared

ineligible for one year. Any player, umpire, or club or league official or

employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in

connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared

permanently ineligible

“The wording has been tweaked over the years, but the core of the rule has been in place for decades and decades,” said MLB’s Media Relations manager Mike Teevan.

In the history of MLB, 19 players have received lifetime bans for betting on the game and eight of those players were 1919 White Sox.

According to Eliot Asinof’s 1963 book Eight Men Out, Arnold Rothstein, a professional gambler with underworld ties, offered White Sox players $10,000 each to fix the 1919 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Shortly after reaching an agreement to take the money, the White Sox players realized that Rothstein might renege on the agreement, but the Sox lost to the Reds 5 games to 3.

A 1921 grand jury found the players innocent of fixing the Series, despite their confessions of taking money from gamblers, but MLB’s newly appointed Commissioner, former federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, permanently banned the players. MLB.com says baseball’s ‘commission’ of owners gave Landis unprecedented power, allowing him to:

investigate, either upon complaint or upon his own initiative, an act,

transaction or practice, charged, alleged or suspected to be detrimental

to the best interest of the national game of baseball, (and to determine and take)

any remedial, preventive or punitive action (he deemed appropriate).

In an effort to restore crediblity to the sport, baseball owners also said the commissioner’s decisions would be final and that the clubs could not challenge the rulings in court.

The SportingNews.com says Landis cited the players’ admission to having ties with professional gamblers as the reason for the lifetime sentences.

Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game, no player

that entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player that sits in a

conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and

means of throwing games are discussed, and does not promptly tell his club about

it, will ever again play professional baseball.

One of those players from 1919, ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson, remains the most accomplished of those 8 banned White Sox. In a 13-year career with the Athletics, Naps/Indians and White Sox, Jackson compiled a .356 career batting average, which remains the third-highest all-time average behind Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, making him a likely candidate for the Hall of Fame before the scandal. According to MLB documents, Jackson, like his other teammates, admitted taking money for his role in altering the series outcome. But he still led his team in batting during that World Series with a .375 average.

Landis died in 1944, and when A.B. “Happy” Chandler became Commissioner in 1945, clubs gained the right to challenge the Commissioner’s decisions.

Today’s Major League Baseball (MLB) doesn’t prohibit players from gambling on other sports, but major leaguers quickly learn that MLB discourages it, according to Teevan who says league conduct presentations routinely center around Rule 21-d, of the player’s misconduct code.

Former U.S. senator George Mitchell’s 2007 Report to MLB Commissioner Bud Selig about steroid use in baseball, commended MLB for posting signs referring to Rule 21 in all major league clubhouses and providing dramatic, role-playing presentations about gambling. Mitchell suggested that MLB do the same in regards to illegal performance-enhancing drugs.

“Our security and facility management department works very closely with each team and its players during Spring Training on a wide variety of issues,” Teevan said. “Our annual Rookie Career Development Program, which is a joint venture between MLB and the Players Association, also touches on important issues with the top prospects from all 30 clubs, and education about gambling is a subject during the presentation.”

Teevan said many officials in the league’s security and investigations departments have experience in law enforcement and that there’s a reason to closely monitor gambling habits of players.

“Gambling is considered an area that could lead to other activities that could affect players’ careers as well their freedom,” Teevan said.

“For educational purposes, for clubs and players, we have used outside speakers who have addressed gambling experiences as a part of our rookie program.”

In 1989, baseball’s all-time hit leader, Pete Rose, joined Jackson on the lifetime ban list when the late Bart Giamatti tossed him out for betting on games in which he played and managed . Rose collected 4,256 hits over a 24-year career with three clubs, and like Jackson, was considered a strong candidate for the Hall of Fame before the ban. He’s the last player, or manager, excommunicated from the game. Prior to Rose, the last MLB figure to be permanently banned from the game was William Cox, owner of the Philadelphia Phillies, exiled by Landis in 1943 for betting on his team’s games.

Rose admitted that he placed bets on his teams in his 2004 book, My Prison Without Bars. but has never officially admitted it to the Commissioner’s Office, so the ban remainsm barring Rose’s participation in any MLB activities.. Rose regularly makes appeals to his fans on peterose.com about lifting the suspension and now owns and operates a souvenir shop in Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas.

National Baseball Hall of Fame communications director Craig Muder said although his organization is independent from MLB, Rose and Jackson are banned from recognition, as well as acceptance, in that shrine, located in Cooperstown, N.Y.

“Pete Rose and Joe Jackson, along with a handful of other players are on baseball's ineligible list,” Muder said, adding that the Commissioner’s decisions on such matters also applies to the Hall.

“Our board of directors feels that it would be incongruous to have a person eligible for the Hall of Fame when he or she is not eligible to participate in organized baseball in any other way,” Muder said.

Last August, when efforts to bring back Rose were rejected by Selig, former MLB Commissioner Faye Vincent, Giamatti’s deputy at the time of Rose’s expulsion from baseball, told Paul Caron of CNN.com that MLB has never reversed lifetime bans.

"Nobody who has ever been thrown out of baseball has ever been reinstated. An owner, the 1919 White Sox, you name it,”said Vincent. “No matter if it's a third-base coach or an all-star, Hall of Fame-type player."

Vincent, who died last month at 75, said he thinks most major leaguers understand the lifetime bans.

"(Hall of Fame pitcher) Tom Seaver once asked me, 'If I'm a Hall of Famer, and I bet on baseball, do I get the same treatment?' I said, 'Yes.' Tom said, 'I get it. If you didn't do that, we would all bet on baseball."